Rising Water Risks for Agricultural Properties

Newsletter

By David McKenzie, Director

The value of agricultural land is increasingly being affected by issues relating to reliable access to water. This is particularly true in the Murray-Darling Basin, which produces 40% of Australia’s agricultural produce worth $24 billion (food and fibre) annually [1], where the rivers are under pressure and rainfall can be unpredictable.

Environment

Environmental factors are contributing to water criticality in the Murray-Darling Basin. Over the last century, there has been a stepped reduction in annual inflow for both the Goulburn (39% reduction from 1891 – 1995/96 average compared to the 1996/97-2019/20 average) and Murray Rivers (36% reduction from 1891 – 1995/96 average compared to the 1996/97-2019/20 average).

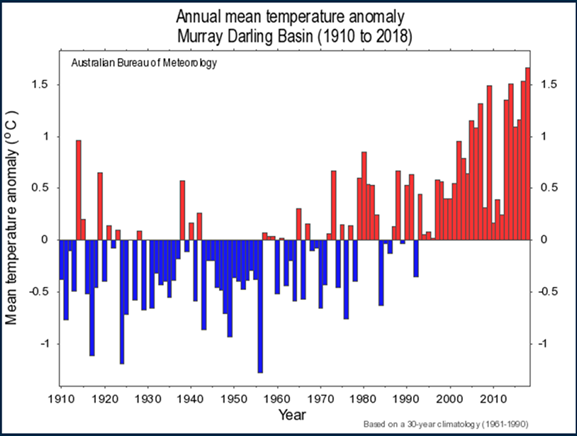

Over a similar period (1910-2018), the annual mean temperature anomaly across the Murray Darling Basin also rose considerably, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Annual mean temperature anomaly Murray Darling Basin (1910-2018) [2]

Allocations and pricing

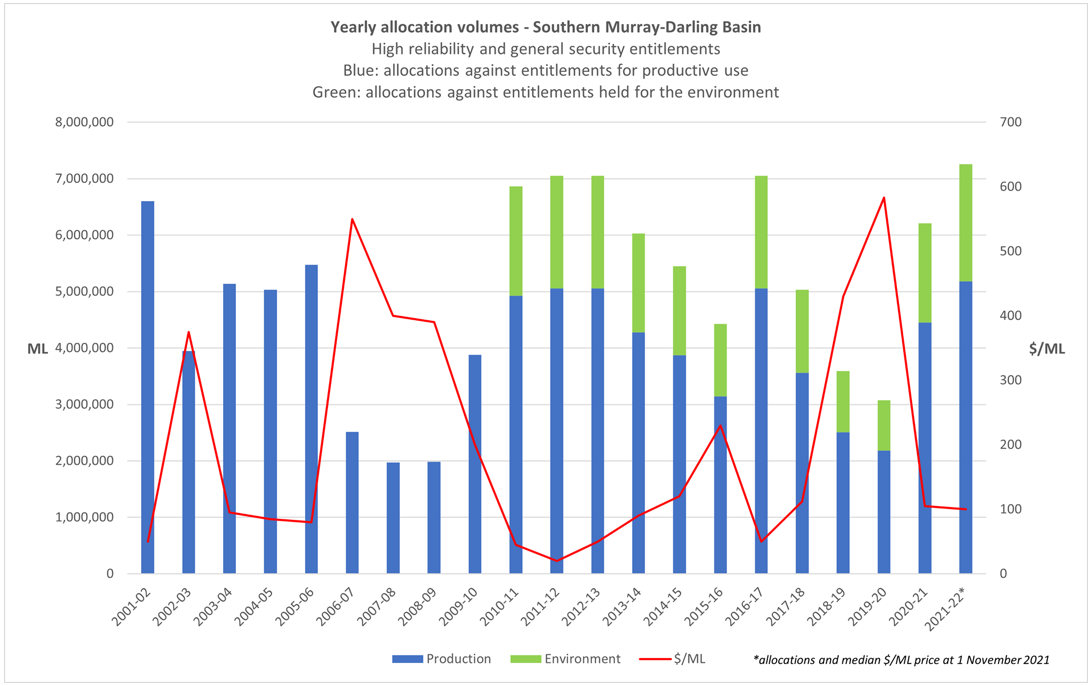

The productive capacity of much agricultural land is underpinned by the reliability of allocation against water shares and entitlements (which in turn are driven by rainfall). This includes broader scarcity for irrigation water affected by increasing competition from other user groups, including the environment, urban and recreational users, and cultural groups. All these issues combine to set the price of both permanent entitlement, and annual allocation. These prices can fluctuate significantly, often at very short notice.

Yearly allocation volumes of high reliability and general security entitlements in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin, mapped against the price per megalitre as seen in figure 2, demonstrate the volatility of the market.

Figure 2: Yearly allocation volumes in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin and the price impact [3]

Policy framework

For decades, there has been a focus on finding a balance for water use between production and the environment. The issue remains highly political.

The Murray Darling Basin Plan (the Plan) puts sustainable diversion limits on water use, which have applied since 2019. Under the Plan, the long-term average environmentally sustainable level of take for surface water is set at 10,873 GL/year and for groundwater the sustainable level of take is 3,324 GL/year. In 2019, there was already significantly more water being taken from the system than these thresholds. The Plan is designed to reduce the actual take, back to the sustainable levels set out above.

Since the Plan came into effect, water has been recovered with a $13 billion budget through direct purchase of water entitlement by the Australian Government, or the exchange of water entitlement for investment in modern infrastructure (on farm and system efficiency projects).

The recovery target was 2,750 GL by 2019, which may be reduced by 650 GL via supply measures or offsets. The water recovery strategy also allows for a further 450 GL reduction by 2024, subject to neutral or improved socio-economic outcomes.

The current state

The Federal Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR)’s offset project analysis has shown 26% of water recovery projects are unable to be delivered without major intervention and there is likely to be a 158 GL shortfall against targets. Further, a number of significant projects are considered at risk, including the Menindee Lakes Project and several contentious constraints projects.

Victorian Farmers Federation (VFF) analysis shows a likely shortfall of 230 GL in 2024 as well as a 45 GL gap overall. The only mechanism available under current legislation to recover the balance will be via buybacks. Extensive socio-economic analysis has proven that buybacks are the most damaging form of water recovery for regional communities and economies. Consequently, this looming recovery gap presents as a significant risk for irrigation dependant regions of the Murray Darling Basin.

Growing deliverability risk for downstream irrigators

The Barmah Choke is a natural narrowing of the Murray River channel, near Echuca. The gradual movement of sediment and sand down the Murray has caused significant loss of channel capacity in the natural waterway – it is silting up. Consequently, there is a growing deliverability risk past the Choke, which has seen capacity reduce from 11,500 ML/day in the 1980s to 9,200 ML/day in 2019[4], and less again in 2021. Additionally, the Darling River has been in drought for many years which has limited transfers from the Menindee Lakes to the Murray system and affects South Australia’s entitlement flow. These factors have combined to put great pressure on the Goulburn River to make up the difference on downstream commitments.

Delivery shortfalls occur when the levels of actual water used are higher than the forecasts because of the time it takes water to travel through the system. These are commonly caused by unexpected spikes in irrigation demands or river evaporation during heatwaves.

System shortfalls occur when the combined capacity of the system is unable to supply all downstream requirements over the full season. One of the key issues is the loss of capacity at the Barmah Choke due to bank erosion and sand levels. When there is a system shortfall, water use below the Barmah Choke (with a capacity now understood to be closer to 7GL/day may need to be rationed to deliver South Australia’s entitlement flow (a minimum of 1,850 GL/year or 5.3GL/day).

What can be done?

There are a range of options to manage the Barmah Choke, including doing nothing to manage the sand, improving banks to control new sediment inputs, physically removing the sand and moving water around via new infrastructure. Each option has its pros and cons.

There have already been some rule changes to protect the Goulburn River, including limiting Goulburn inter-valley trade (capped at 40 GL/month) and removing tagged water provisions. However, while these changes remove the opportunity for tagged water to sneak past the choke, they also exacerbate delivery shortfall risk in heatwaves.

What it means for the agriculture sector

Agricultural landowners, developers and investors need to consider water access issues in the context of the Murray Daring Basin Plan and the likely recovery shortfall and buyback demand.

Agricultural land value will continue to be affected by deliverability risks that cannot be fully mitigated, and that these are likely to increase going forward.

The new rules will partly insulate districts above the Barmah Choke, however there will continue to be significant pressure on low value irrigation below the Choke and increasing pressure for user groups between the Choke and the SA border.

Between climate change, elevated competition for water, uncertainty about fulfilment of recovery targets in the Basin Plan, and growing deliverability risks in the lower Murray region, there is little doubt that the classes of water that can be traded along the length of the Murray River (with all attendant access rights), will be increasingly sought, and likely to experience significant upward price pressure in the medium to long term.

[1] Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA)

[2] Bureau of Meteorology

[3] Claire Miller Consulting

[4] Managing Delivery Risks in the River Murray System (MDBA)

DISCLAIMER

This material is produced by Opteon Property Group Pty Ltd. It is intended to provide general information in summary form on valuation related topics, current at the time of first publication. The contents do not constitute advice and should not be relied upon as such. Formal advice should be sought in particular matters. Opteon’s valuers are qualified, experienced and certified to provide market value valuations of your property. Opteon does not provide accounting, specialist tax, investment or financial advice.

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.